|

Mike Terry's Black Belt School Of Script-Fu Author Mike Terry |

The Road To Script-Fu Mastery

|

|

|

So, little grasshopper, you have found Gimp, and you want to learn of its secrets? More specifically, you wish to learn of its fantastic scripting abilities, no? You are perhaps tantalized at the prospect of automating image-editing drudgery, or maybe you seek the kind of precision in your work that only a well-written script can achieve.... Well, you have come to the right place, my friend, as Mike Terry's Black Belt School of Script-Fu can train you in the not-so-ancient art of Script-Fu. Course OutlineIn this training course, we'll introduce you to the fundamentals of Scheme necessary to use Script-Fu, and then build a handy script that you can add to your toolbox of scripts. The script prompts the user for some text, then creates a new image sized perfectly to the text. We will then enhance the script to allow for a buffer of space around the text. Meet Your InstructorLet me first confess that I am currently only a yellow-belt of this art, and as such, can only take you so far. However, together, we can press on and reach new heights. If I err, omit some important detail in this training or am just plain wrong about something, please email me so I may correct it. Similarly, if you have tips or suggestions on how to improve your training, please forward them to me. I hope you benefit from this training, and may you soon become a Master of Script-Fu! AudienceThese training sessions are intended for the beginning Script-Fu'er. When I heard that Gimp was scriptable, I got very excited, and wanted to dive right in. Unfortunately, the tutorials were scant and incomplete, especially if you knew no Scheme (like I didn't). After about two days of trying to force my square peg of C/C++ knowledge into the round hole of Scheme, I reckoned a tutorial from the ground-up, chock-full of demos, would do the new Script-Fu'er a lot of good. Currently, then, the tutorial is really aimed at the beginner, but as I learn more, I will expand it so we can all be Script-Fu Masters! Your suggestions and complaints are welcome:

| |

Lesson 1: Getting Acquainted With Scheme

|

|

Before We Begin...Before we begin, we have to make sure we're all at the same training hall. That is, you must have Gimp installed and fully functional. To get the latest version of Gimp, or for pointers on installing it and getting it running, we refer you to Gimp's central home page. (This tutorial was written using Gimp 1.0.0.) Let's Start Scheme'ing |

|

|

The first thing to learn is that: · Every statement in Scheme is surrounded by parentheses (). The second thing you need to know is that: · The function name/operator is always the first item in the parentheses, and the rest of the items are parameters to the function. However, not everything enclosed in parentheses is a function -- they can also be items in a list -- but we'll get to that later. This notation is referred to as prefix notation, because the function prefixes everything else. If you're familiar with postfix notation, or own a calculator that uses Reverse Polish Notation (such as most HP calculators), you should have no problem adapting to formulating expressions in Scheme. The third thing to understand is that: · Mathematical operators are also considered functions, and thus are listed first when writing mathematical expressions. This follows logically from the prefix notation that we just mentioned. Examples Of Prefix, Infix, And Postfix NotationsHere are some quick examples illustrating the differences between prefix, infix, and postfix notations. We'll add a 1 and 3 together: · Prefix notation: + 1 3 (the way Scheme will want it) · Infix notation: 1 + 3 (the way we "normally" write it) · Postfix notation: 1 3 + (the way many HP calculators will want it) Practicing In SchemeNow, grasshopper, let's practice what we have just learned. Start up Gimp, if you have not already done so, and choose |

|

Watch Out For Extra ParensIf you're like me, you're used to being able to use extra parentheses whenever you want to -- like when you're typing a complex mathematical equation and you want to separate the parts by parentheses to make it clearer when you read it. In Scheme, you have to be careful and not insert these extra parentheses incorrectly. For example, say we wanted to add 3 to the result of adding 5 and 6 together: 3 + (5 + 6) + 7= ? Knowing that the + operator can take a list of numbers to add, you might be tempted to convert the above to the following: (+ 3 (5 6) 7) However, this is incorrect -- remember, every statement in Scheme starts and ends with parens, so the Scheme interpreter will think that you're trying to call a function named "5" in the second group of parens, rather than summing those numbers before adding them to 3. The correct way to write the above statement would be: (+ 3 (+ 5 6) 7) Make Sure You Have The Proper Spacing, TooIf you are familiar with other programming languages, like C/C++, Perl or Java, you know that you don't need white space around mathematical operators to properly form an expression: 3+5, 3 +5, 3+ 5 These are all accepted by C/C++, Perl and Java compilers. However, the same is not true for Scheme. You must have a space after a mathematical operator (or any other function name or operator) in Scheme for it to be correctly interpreted by the Scheme interpreter. Practice a bit with simple mathematical equations in the Script-Fu Console until you're totally comfortable with these initial concepts. |

Lesson 2: Of Variables And Functions

|

|

|

So, my student, you are curious and want to know about variables and functions? Such vigor in your training -- I like it. VariablesNow that we know that every Scheme statement is enclosed in parentheses, and that the function name/operator is listed first, we need to know how to create and use variables, and how to create and use functions. We'll start with the variables. Declaring VariablesAlthough there are a couple of different methods for declaring variables, the preferred method is to use the |

|

|

|

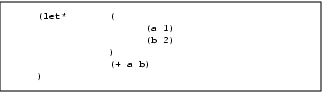

(let* ( (a 1) (b 2) ) (+ a b) ) |

|

|

Note: You'll have to put all of this on one line if you're using the console window. In general, however, you'll want to adopt a similar practice of indentation to help make your scripts more readable. We'll talk a bit more about this in the section White Space. This declares two local variables, What Is A Local Variable?You'll notice that we wrote the summation ( This is because the The General Syntax Of let*The general form of a (let* ( variables ) expressions ) where variables are declared within parens, e.g., ( White SpacePreviously, we mentioned the fact that you'll probably want to use indentation to help clarify and organize your scripts. This is a good policy to adopt, and is not a problem in Scheme -- white space is ignored by the Scheme interpreter, and can thus be liberally applied to help clarify and organize the code within a script. However, if you're working in Script-Fu's Console window, you'll have to enter an entire expression on one line; that is, everything between the opening and closing parens of an expression must come on one line in the Script-Fu Console window. Assigning A New Value To A VariableOnce you've initialized a variable, you might need to change its value later on in the script. Use the (let* ( (theNum 10) ) (set! theNum (+ theNum \ theNum)) ) Try to guess what the above statement will do, then go ahead and enter it in the Script-Fu Console window. |

|

Note: The "\" indicates that there is no line break. Ignore it (don't type it in your Script-Fu console and don't hit Enter), just continue with the next line. FunctionsNow that you've got the hang of variables, let's get to work with some functions. You declare a function with the following syntax: (define (name param-list) expressions ) where (define (AddXY inX inY) (+ inX inY) )

If you've programmed in other imperative languages (like C/C++, Java, Pascal, etc.), you might notice that a couple of things are absent in this function definition when compared to other programming languages. · First, notice that the parameters don't have any "types" (that is, we didn't declare them as strings, or integers, etc.). Scheme is a type-less language. This is handy and allows for quicker script writing. · Second, notice that we don't need to worry about how to "return" the result of our function -- the last statement is the value "returned" when calling this function. Type the function into the console, then try something like: (AddXY (AddXY 5 6) 4) |

Lesson 3: Lists, Lists And More Lists

|

|

|

We've trained you in variables and functions, young Script-Fu'er, and now we must enter the murky swamps of Scheme's lists. Are you ready for the challenge? Defining A ListBefore we talk more about lists, it is necessary that you know the difference between atomic values and lists. You've already seen atomic values when we initialized variables in the previous lesson. An atomic value is a single value. So, for example, we can assign the variable "x" the single value of 8 in the following statement:

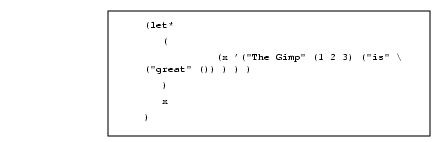

(We added the expression A variable may also refer to a list of values, rather than a single value. To assign the variable

Try typing both statements into the Script-Fu Console and notice how it replies. When you type the first statement in, it simply replies with the result: 8 However, when you type in the other statement, it replies with the following result: (1 3 5) When it replies with the value The syntax to define a list is: '(a b c) where An empty list can be defined as such: '() or simply: () Lists can contain atomic values, as well as other lists: |

|

|

|

|

Notice that after the first apostrophe, you no longer need to use an apostrophe when defining the inner lists. Go ahead and copy the statement into the Script-Fu Console and see what it returns. You should notice that the result returned is not a list of single, atomic values; rather, it is a list of a literal (" How To Think Of ListsIt's useful to think of lists as composed of a "head" and a "tail." The head is the first element of the list, the tail the rest of the list. You'll see why this is important when we discuss how to add to lists and how to access elements in the list.

Creating Lists Through Concatenation

|

|

|

|

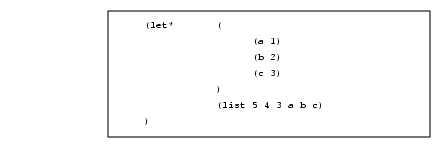

|

This code creates the list Accessing Values In A ListTo access the values in a list, use the functions The car Function

(car '("first" 2 "third")) which is: "first" The cdr function

(cdr '("first" 2 "third")) returns: (2 "third") whereas the following: (cdr '("one and only")) returns: () Accessing Other Elements In A ListOK, great, we can get the first element in a list, as well as the rest of the list, but how do we access the second, third or other elements of a list? There exist several "convenience" functions to access, for example, the head of the head of the tail of a list ( The basic naming convention is easy: The a's and d's represent the heads and tails of lists, so (car (cdr (car x) ) ) could be written as:

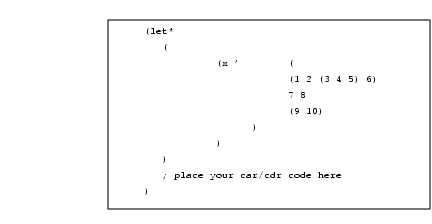

To view a full list of the list functions, refer to Appendix C, which lists the available functions for the version of Scheme used by Script-Fu. To get some practice with list-accessing functions, try typing in the following (except all on one line if you're using the console); use different variations of |

|

|

|

|

Try accessing the number 3 in the list using only two function calls. If you can do that, you're on your way to becoming a Script-Fu Master! | |

Lesson 4: Your First Script-Fu Script

|

|

|

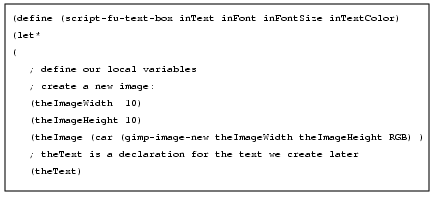

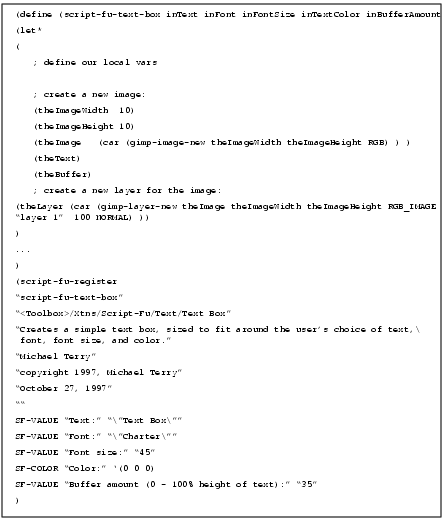

Do you not need to stop and catch your breath, little grasshopper? No? Well then, let's proceed with your fourth lesson -- your first Script-Fu Script. Creating A Text Box ScriptOne of the most common operations I perform in Gimp is creating a box with some text in it for a web page, a logo or whatever. However, you never quite know how big to make the initial image when you start out. You don't know how much space the text will fill with the font and font size you want. The Script-Fu Master (and student) will quickly realize that this problem can easily be solved and automated with Script-Fu. We will, therefore, create a script, called Text Box, which creates an image correctly sized to fit snugly around a line of text the user inputs. We'll also let the user choose the font, font size and text color. Getting StartedEditing And Storing Your ScriptsUp until now, we've been working in the Script-Fu Console. Now, however, we're going to switch to editing script text files. Where you place your scripts is a matter of preference -- if you have access to Gimp's default script directory, you can place your scripts there. However, I prefer keeping my personal scripts in my own script directory, to keep them separate from the factory-installed scripts. In the . The Bare EssentialsEvery Script-Fu script defines at least one function, which is the script's main function. This is where you do the work. Every script must also register with the procedural database, so you can access it within Gimp. We'll define the main function first:

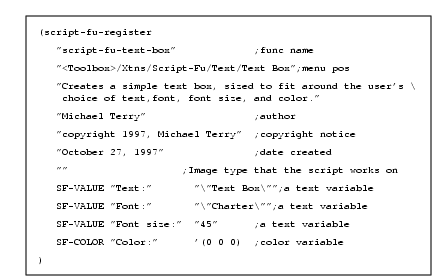

Here, we've defined a new function called Naming ConventionsScheme's naming conventions seem to prefer lowercase letters with hyphens, which I've followed in the naming of the function. However, I've departed from the convention with the parameters. I like more descriptive names for my parameters and variables, and thus add the " It's Gimp convention to name your script functions Registering The FunctionNow, let's register the function with Gimp. This is done by calling the function Here's the listing for registering this function (I will explain all its parameters in a minute): |

|

|

|

|

If you save these functions in a text file with a |

|

|

|

|

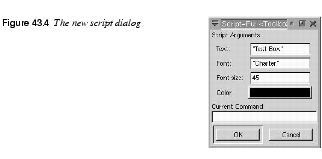

If you invoke this new script, it won't do anything, of course, but you can view the prompts you created when registering the script (more information about what we did is covered next). |

|

|

|

|

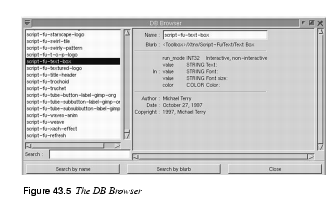

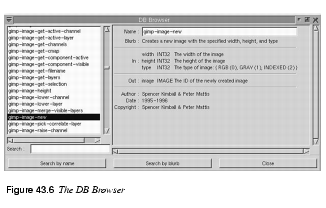

Finally, if you invoke the DB Browser (the procedural database browser -- |

|

|

|

Steps For Registering The ScriptTo register our script with Gimp, we call the function The Required Parameters· The name of the function we defined. This is the function called when our script is invoked (the entry-point into our script). This is necessary because we may define additional functions within the same file, and Gimp needs to know which of these functions to call. In our example, we only defined one function, · The location in the menu where the script will be inserted. The exact location of the script is specified like a path in Unix, with the root of the path being either If your script does not operate on an existing image (and thus creates a new image, like our Text Box script will), you'll want to insert it in the toolbox menu -- this is the menu in Gimp's main window (where all the tools are located: the selection tools, magnifying glass, etc.). If your script is intended to work on an image being edited, you'll want to insert it in the menu that appears when you right-click on an open image. The rest of the path points to the menu lists, menus and sub-menus. Thus, we registered our Text Box script in the Text menu of the Script-Fu menu of the Xtns menu of the toolbox ( If you notice, the Text sub-menu in the Script-Fu menu wasn't there when we began -- Gimp automatically creates any menus not already existing. · A description of your script. I'm not quite sure where this is displayed. · Your name (the author of the script). · Copyright information. · The date the script was made, or the last revision of the script. · The types of images the script works on. This may be any of the following: RGB, RGBA, GRAY, GRAYA, INDEXED, INDEXEDA. Or it may be none at all -- in our case, we're creating an image, and thus don't need to define the type of image on which we work. Registering The Script's ParametersOnce we have listed the required parameters, we then need to list the parameters that correspond to the parameters our script needs. When we list these params, we give hints as to what their types are. This is for the dialog which pops up when the user selects our script. We also provide a default value. This section of the registration process has the following format:

The different parameter types, plus examples, are listed in Table 43.1.

| |

Lesson 5: Giving Our Script Some Guts

|

|

|

You show great dedication to your studies, my student. Let us thus continue with your training and add some functionality to our script. Creating A New ImageIn the previous lesson, we created an empty function and registered it with Gimp. In this lesson, we want to provide functionality to our script -- we want to create a new image, add the user's text to it and resize the image to fit the text exactly. Once you know how to set variables, define functions and access list members, the rest is all downhill -- all you need to do is familiarize yourself with the functions available in Gimp's procedural database and call those functions directly. So fire up the DB Browser and let's get cookin'! Let's begin by making a new image. We'll create a new variable, |

|

|

|

|

As you can see from the DB Browser, the function |

|

|

|

|

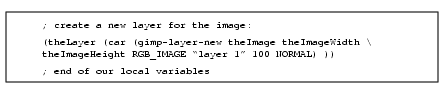

Note: We used the value You should also notice that we took the head of the result of the function call. This may seem strange, because the database explicitly tells us that it returns only one value -- the ID of the newly created image. However, all Gimp functions return a list, even if there is only one element in the list, so we need to get the head of the list. Adding A New Layer To The ImageNow that we have an image, we need to add a layer to it. We'll call the |

|

|

|

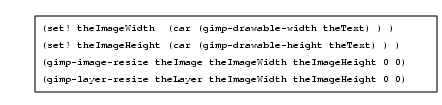

Once we have the new layer, we need to add it to the image: (gimp-image-add-layer theImage theLayer 0) Now, just for fun, let's see the fruits of our labors up until this point, and add this line to show the new, empty image: (gimp-display-new theImage) Save your work, select Adding The TextGo ahead and remove the line to display the image (or comment it out with a ; as the first character of the line). Before we add text to the image, we need to set the background and foreground colors so that the text appears in the color the user specified. We'll use the (gimp-palette-set-background '(255 255 255) ) (gimp-palette-set-foreground inTextColor) With the colors properly set, let's now clean out the garbage currently in the image. We'll select everything in the image, and call clear: (gimp-selection-all theImage) (gimp-edit-clear theImage theLayer) (gimp-selection-none theImage) With the image cleared, we're ready to add some text: Now that we have the text, we can grab its width and height and resize the image and the image's layer to the text's size: |

|

|

|

|

If you're like me, you're probably wondering what a drawable is when compared to a layer. The difference between the two is that a drawable is anything that can be drawn into; a layer is a more specific version of a drawable. In most cases, the distinction is not important. With the image ready to go, we can now re-add our display line: (gimp-display-new theImage) Save your work, refresh the database and give your first script a run! You should get something like Figure 43.7. |

|

|

|

Clearing The Dirty FlagIf you try to close the image created without first saving the file, Gimp will ask you if you want to save your work before you close the image. It asks this because the image is marked as dirty, or unsaved. In the case of our script, this is a nuisance for the times when we simply give it a test run and don't add or change anything in the resulting image -- that is, our work is easily reproducible in such a simple script, so it makes sense to get rid of this dirty flag. To do this, we can clear the dirty flag after displaying the image: (gimp-image-clean-all theImage) This will dirty count to 0, making it appear to be a "clean" image. Whether to add this line or not is a matter of personal taste. I use it in scripts that produce new images, where the results are trivial, as in this case. If your script is very complicated, or if it works on an existing image, you will probably not want to use this function. | |

Lesson 6: Extending The Text Box Script

|

|

|

Your will and determination are unstoppable, my eager student. So let us continue your training. Handling Undo CorrectlyWhen creating a script, you want to give your users the ability to undo their actions, should they make a mistake. This is easily accomplished by calling the functions If you are creating a new image entirely, it doesn't make sense to use these functions because you're not changing an existing image. However, when you are changing an existing image, you most surely want to use these functions. As of this writing, undoing a script works nearly flawlessly when using these functions. However, it does seem to have some trouble undoing everything, now and then, and it seems to have the hardest time when calling another script that doesn't itself call these functions. Extending The Script A Little MoreNow that we have a very handy-dandy script to create text boxes, let's add two features to it: · Currently, the image is resized to fit exactly around the text -- there's no room for anything, like drop shadows or special effects (even though many scripts will automatically resize the image as necessary). Let's add a buffer around the text, and even let the user specify how much buffer to add as a percentage of the size of the resultant text. · This script could easily be used in other scripts that work with text. Let's extend it so that it returns the image and the layers, so other scripts can call this script and use the image and layers we create. Modifying The Parameters And The Registration FunctionTo let the user specify the amount of buffer, we'll add a parameter to our function and the registration function: |

|

|

|

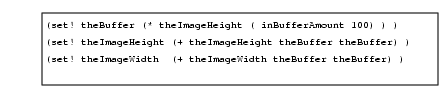

Adding The New CodeWe're going to add code in two places: right before we resize the image, and at the end of the script (to return the new image, the layer and the text). After we get the text's height and width, we need to resize these values based on the buffer amount specified by the user. We won't do any error checking to make sure it's in the range of 0-100% because it's not life-threatening, and because there's no reason why the user can't enter a value like "200" as the percent of buffer to add. |

|

|

|

|

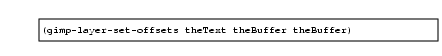

All we're doing here is setting the buffer based on the height of the text, and adding it twice to both the height and width of our new image. (We add it twice to both dimensions because the buffer needs to be added to both sides of the text.) Now that we have resized the image to allow for a buffer, we need to center the text within the image. This is done by moving it to the (x, y) coordinates of ( |

|

|

|

|

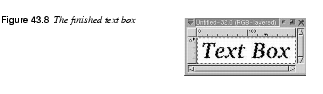

Go ahead and save your script, and try it out after refreshing the database. You should now get a window like Figure 43.8. |

|

|

|

|

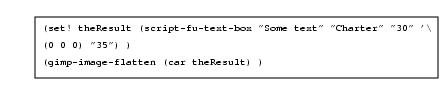

All that is left to do is return our image, the layer, and the text layer. After displaying the image, we add this line: (list theImage theLayer theText) This is the last line of the function, making this list available to other scripts that want to use it. To use our new text box script in another script, we could write something like the following: |

|

|

|

|

Congratulations, my student, you are on your way to your Black Belt of Script-Fu! | |

| Frozenriver Digital Design http://www.frozenriver.nu Voice: +46 (0)31 474356 Fax: +46 (0)31 493833 support@frozenriver.com |

Publisher Coriolis http://www.coriolis.com |